Members of the community can now view the Harlin Museum’s Ozark Heritage Exhibit featuring L.L. Broadfoot’s Pioneers of the Ozarks, a collection of art by the accomplished late Shannon County artist.

Broadfoot is best known for his enigmatic people, places and traditions of the Ozarks region, while also offering a firsthand narrative in his writings that often accompanies his works.

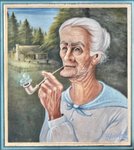

One such narrative on display at the Harlin Museum, 405 Worcester St. in West Plains, accompanies a portrait of Katherine Burk, who was born Feb. 13, 1829 in Timber, Shannon County.

The woman, 111 years old at the time, raised in the Ozark hills was known as the oldest person in the area, according to Broadfoot.

“I have smoked an’ chawed terbacker ever since I wuz a little girl, an’ I don’t believe terbacker hurts a body either, if they use it right, but the way young people use it nowadays, I think it hurts ‘em,” Broadfoot quotes Burk as telling him. “They sit around, suckin’ cigarettes and draw the smoke down in their lungs, an’ soon they get to coughing’ an’ wheezin’ in their lungs like a pig that’s sick with cholera, an’ their health is gone an’ they die young.

“My pappy an’ mammy smoked an’ chawed too, but they smoked a clay pipe like I do, an’ we never smoked or chawed nothin’ only what we raised ourselves.

“I reckon I’m ol’-fashioned an’ foagy, but I believe the ol’ way of life is best.”

She went on to describe her beliefs regarding what some might call superstitions, calling into question the popular definition of “witch.” She told Broadfoot she believed in moon signs and witches, and that once, folks considered her to be a witch — adding, “Lots of people don’t know what a witch is.”

“If you don’t know, I’ll tell ye,” she said to Broadfoot. “A witch is an ol’ person — usually a womern, with humpback, an’ goosenecked with long chin an’ nose, with stringy, frizzlie hair, deep wrinkles in her face, an’ her eyes as glassy an’ glairy as a dyin’ calf’s eye, an’ sets aroun’ or snoops aroun’ an’ says nothin’ to nobody, an’ has the power to send their spirit away to work around the homes of others an’ do things.”

She said the reason why the witches don’t say much is “‘cause their mind an’ spirit is allers away somewheres else,” and the powers of witchcraft are reserved for those women at least 70 years old.

She told of the troubles she’d seen caused by witches: knots tied in horses’ and cows’ tails, feathers plucked out of a rooster’s tail. To stop such incidences from occurring, her family had a tried and true method, she averred.

“The witch usually has a rabbit to carry her spirit here an’ there, doin’ devilment, an’ we watched our chance to shoot an’ kill the rabbit, or we didn’t kill the rabbit, we would keep our minds good an’ strong on the person we though wuz the witch while we stuck a dishrag full of pins an’ throw it in the fire an’ burn it, or take a ball of yarn an’ pierce it with a darnin’ needle with our minds concentrated on that certain ol’ witch,” she explained. “We would get ‘em that way.”

BROADFOOT’S ROOTS

Broadfoot was born on Sept. 10, 1891, in a log cabin home high in the hills of Shannon County along the wild and rugged Current River near modern-day Eminence, to James Henderson Broadfoot and Elizabeth Henry Cagle Broadfoot.

His parents came to Missouri early on in their lives from the Smoky Mountains of Tennessee and homesteaded a 40-acre tract of government land in the Ozarks, full of heavy timber and underbrush. From this wilderness, they procured their living and raised their family. Lennis, or L.L., as he would come to be known in his later years was one of 13 children.

From an early age, he loved creating art and aspired to become an artist, but he was discouraged both at home and at school.

According to the Harlin Museum, he persisted and developed his talent at every available moment by keeping his pockets filled with paper — sketching home scenes and neighbors who would sit around the fireplace and swap tales of the old days.

However, from a very early age, character studies were his specialty.

His need to create art inspired him to travel and after his mother died in 1909, he traveled across the U.S., headed west, worked as a cowboy and practiced drawing portraits along the way. In 1912, he married his first wife, Mary Ethyl Randolph, also from Shannon County.

They had four sons — Lindell, Dane, Carmel and Verril — before divorcing in 1933.

For 20 years, he did odd jobs and never abandoned his love for sketching. He settled in Great Falls, Mont., for five years and met well-known western artist Charles Russell, who encouraged him to pursue his artistic talent. Broadfoot enrolled in the Federal School, Inc., a correspondence art school, later known as the Art Instruction, Inc., and then worked as a commercial artist in southern California during the early 1930s.

STUDY IN THE OZARKS

It was from his studio in Pasadena, Calif., that he decided to return to the Ozarks in November 1936, determined to complete what he saw as his life’s work: character studies of the Ozarks pioneers and capturing the region he knew and loved through his art. He drew scores of Ozarks natives and hill country activities while recording stories about each one, such as Burk’s narrative about witches, in the written word.

He describes the purpose of his volume of work: “to preserve a true picture record of the pioneers of the hills, their strange customs of living that are so rapidly vanishing, and a life that is so different from anything known to modern folk, that it should be educational, especially to the younger generation who know nothing of the joys and hardships of primitive ways.”

In 1944, Broadfoot found a publisher for “Pioneers of the Ozarks,” a book featuring 88 charcoal drawings and accompanying stories featuring people of the Ozarks. Shortly, thereafter, he attempted to publish a second book, “Stoney of the Wildwoods,” which was a work of fiction based on the real-life man, Jess Thompson, who appears in the “Pioneers of the Ozarks” series.

The story follows the fictional protagonist, named Stoney, who is known for his uncanny abilities as a stone-throwing-marksman on his adventures throughout the wild Ozark hills. Unfortunately, the book was never published in the author’s lifetime. The manuscript, and its accompanying artwork, are now a part of the Harlin Museum’s permanent collection of Broadfoot works.

In 1935, while in Cheyenne, Wyo., Broadfoot met Elva Etta Brown from Kirksville who became his constant companion.

They later married on June 22, 1943, and settled in February 1944 in Salem, Dent County, where they opened the Wildwood Art Gallery in their residence.

Broadfoot spent the rest of his life promoting and exhibiting his artwork at his gallery in Salem, as well as at nearby Montauk State Park and in St. Louis. He fervently searched for a home for his art, lobbying the Missouri State Park Board and the National Park Service, with hopes of keeping the entire collection together and establishing a permanent gallery in the Ozarks region.

His considerable efforts towards the creation of the Ozark Scenic National Riverways, including his correspondence with Congressman Richard H. Ichord and Senator Stuart Symington, were largely motivated by his search for a permanent gallery for his work.

Broadfoot died March 17, 1984, and is buried at Cedar Grove Cemetery in Salem.

In 2005, Broadfoot’s son, Dane, donated the Broadfoot collection of over 200 works of art, along with original manuscripts and Broadfoot’s collection of personal correspondence to the Harlin Museum in West Plains, where it currently resides on rotating display.

The Harlin Museum will have Broadfoot’s Pioneer of the Ozarks available for the public to view during business hours, noon to 4 p.m. Thursdays through Sundays, until July 31.

The Harlin Museum contributed to this article.